A View on Buddhism (TANTRIC SYMBOLS)

INTRODUCTION

For the untrained, especially the symbolism in tantra can be extremely confusing. However, it should be noted that in modern psychology, Freud and Jung have clarified many aspects of the sub-consciousness in terms of symbolism. In Buddhism, something like sub-consciousness is an impossibility by definition - an awareness without consciousness does not make sense, but there are certainly areas of our mind we are only barely aware of. In order to access these more hidden and subtle aspects of our mind, symbols can be very effective in mind transformation.

As Jean Shinoda Bolen writes in The Tao of Psychology:

|

The very last word of this quote is important in the entire concept of tantra; it can be efficient in enhancing spiritual progress, but if used unskilful, it can lead to madness like personal 'crusades' and 'holy wars'. This presents another good reason for the traditional secrecy of tantric practice and reliance on a true spiritual master.

Another important aspect is the fact that the Buddha clearly explained that "meaningless ritual" should not be practised. So by definition, one could say that ritual in Buddhism must be filled with (symbolic) meaning.

Most of below symbols are taken from the Tibetan traditions, as they can be considered to have preserved the most complete set of tantric teachings.

The Vajra is a very important symbol in Buddhist tantra. In fact, the Tantra teachings are even referred to as the Vajrayana or Vajra-vehicle. The vajra is probably a derivation of a weapon and a sceptre, and may have its origins in the trident and a mendicants' staff, and symbolises being indestructible, therefore sometimes compared to a diamond.

The Vajra is a very important symbol in Buddhist tantra. In fact, the Tantra teachings are even referred to as the Vajrayana or Vajra-vehicle. The vajra is probably a derivation of a weapon and a sceptre, and may have its origins in the trident and a mendicants' staff, and symbolises being indestructible, therefore sometimes compared to a diamond.

To give an impression of the vast symbolic meaning of many objects used in Tibetan Buddhist tantra, below is a summary excerpt from the excellent book "The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Symbols and Motifs" by Robert Beer.

"At the centre of the vajra is a flattened sphere representing the dharmata as the 'sphere of actual reality'. This sphere is sealed within by the syllable HUM, whose three component sounds represent freedom from karma (Hetu), freedom from conceptual thought (Uha) and the groundlessness of all dharmas (M). On either side of the central hub are three rings [which] symbolise the spontaneous bliss of Buddha nature as emptiness, signlessness and effortlessness. Emerging from the three rings on either side are two eight-petalled lotuses. The sixteen petals represent the sixteen modes of emptiness. The upper lotus petals also represent the eight bodhisattvas, and the eight lower petals, the eight female consorts. Above the lotus bases are another series of three pearl-like rings, which collectively represents the six perfections of patience, generosity, discipline, effort, meditation and wisdom. A full moon disc crowns each of the lotuses, symbolising the full realisation of absolute and relative bodhicitta Emerging from the moon discs are five tapering prongs, forming a spherical cluster or cross. The four [outer] curved prongs curve inwards to the central prong, symbolising that the four aggregates of form, feeling, perception and motivation depend upon the fifth aggregate of consciousness. The five upper prongs of the vajra represent the Five Buddhas (Akshobhya, Vairochana, Ratnasambhava, Amitabha and Amogasiddhi), and the unity of their five wisdoms, attributes and qualities. The five lower prongs represent the female consorts of the Five Buddhas (Mamaki, Lochana, Vajradhatvishvari, Pandara and Tara) and the unity of their qualities and attributes.

The Five Buddhas and their consorts symbolise the elimination of the five aggregates of personality. The ten prongs together symbolise the ten perfections (the six mentioned above plus skilful means, aspiration, inner strength, and pure awareness); the 'ten grounds' or progressive levels of realisation of a bodhisattva; and the ten directions. Each of the outer prongs arise from the heads of Makaras (sea monster). The four Makaras symbolise the four immeasurables (compassion, love, sympathetic joy and equanimity); the four doors of liberation (emptiness, signlessness, wishlessness and lack of composition); the conquest of the four Maras (emotional defilements, passion, death, divine pride and lust); the four activities or karmas; the four purified elements (air, fire, water, earth); and the four joys (joy, supreme joy, the joy of cessation and innate joy).

The tips at the end of the central prong may be shaped like a tapering pyramid or four-faceted jewel, which represents Mount Meru as the axial centre of both the outer macrocosm and inner microcosm. The twin faces of the symmetrical vajra represent the unity of relative and absolute truth."

The above describes the most common version of the five-pronged vajra. There are also the one-pronged, three-pronged and nine-pronged vajra, the double vajra (see left) etc., each with their own extensive symbolism....

THE BELL

In tantric rituals, the Vajra is normally held in the right hand, and the Bell in the left. In this combination, the Vajra symbolises method, bliss and male aspects, and the Bell symbolises wisdom, emptiness, the female aspect. The bell as a whole symbolises the sound of the Dharma and is often used in tantric rituals to offer sound.

In tantric rituals, the Vajra is normally held in the right hand, and the Bell in the left. In this combination, the Vajra symbolises method, bliss and male aspects, and the Bell symbolises wisdom, emptiness, the female aspect. The bell as a whole symbolises the sound of the Dharma and is often used in tantric rituals to offer sound.

The Bell is traditionally topped by a half-vajra (the 5 spokes are the five forms of mystical wisdom), and below is the face of Viarocana - the incarnation of universal truth (Dharma). On the shoulder of the bell are 8 lotus petals with syllables in them; the lotus leaves represent the 8 great Bodhisattvas and the syllables are their consorts. As you may suspect by now, each and every detail of the bell has an elaborate symbolic meaning. The whole of the bell can even symbolise a complete mandala.

Whenever one holds these objects, one should try to remember these symbolic meanings and gradually familiarise the mind with the idea; this is the main idea behind meditation.

SOME OTHER TANTRIC IMPLEMENTS

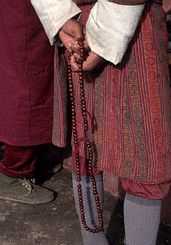

An implement carried around by most Tibetans is the Mala or a rosary of prayer beads. These are not unlike the Christian rosary, or the beads used in Islam and Hinduism. They are used to focus ones' mind on the recitation of mantras, and to count them as part of a practice.

The story of the beads' origin is as follows: “Sakyamuni, the founder of Buddhism, paid a visit to king Vaidunya…Sakya directed him to thread 108 seeds of the Bodhi tree on a string, and while passing them between his fingers to repeat… ‘Hail to the Buddha, the law, and the congregation’… (2,000) times a day (Dubin)” (from this page not all the info here is correct though).

There are for example practices for which one is required to recite 100,000 mantras; obviously a simple counter is needed to keep track of this huge number. The Tibetan mala usually has at least 108 beads - this number probably originates to the 108 names for Hindu deities (incidentally, the same number is used in Islam to refer to God). See also an interesting Hindu article on the number of 108.

Tibetans often attach strings to their malas which have little sliding rings on them, these are to keep count of the number of malas; in such a way one can count up to 10,000 or even more on one mala.

(The word 'rosary,' which has obvious similarities to the mala, is said to have come from 'japa mala.' When Roman explorers came into India and encountered the mala, they heard 'jap mala' instead of 'japa mala.' 'Jap' means 'rose,' and the mala was carried back to the Roman Empire as 'rosarium,' and into English as 'rosary.')

See here for an interesting page on the Mala. And What Not to Do with a Mala. You can even download a Mala Manual here in PDF format.

Some exceptional malas are made by a friend of mine...The Khatvanga (Skt.) could be called a magic wand or magicians' stick and represents the 'magic powers' or siddhis (Skt.) of an accomplished tantric practitioner.

"The shaft of the khatvangha has eight sides which represent the Noble Eightfold path (the fourth Noble Truth) and the eight classes of protectors. At the end of the shaft is a dorje representing totality and completion. Along the shaft of the khatvangha are crossed dorjes, a gTérbum and three heads. The crossed dorjes are symbolic of the indestructibility of beginningless wisdom mind. The gTérbum is symbolic of wealth and enrichment. The three heads – one freshly severed, one rotting and one a skull – are the symbols of the three spheres of being, chö-ku, long-ku and trül-ku [Nirmanakaya, the middle one represents the Sambhogakaya, and the top one is a skull, representing the Dharmakaya] which are unified by the shaft of the khatvangha demonstrating their inseparability. Streamers of the colours of the five elements hang from the khatvangha, as well as a bell and dorje which represent emptiness and form. At the top of the khatvangha are the three prongs which pierce the fabric of attraction, aversion and indifference. Hanging from the prongs are two pairs of rings. These signify the four philosophical extremes that are denied by Dharma: eternalism and nihilism, monism and dualism. Finally the khatvangha is surmounted by wisdom fire – the fire that burns self-protection, justification and referentiality."

The top of the kathvanga can be formed by a vajra or a trident (often depicted with flames around it)

The Tibetan Bumpa is a ritual vase which represents the palace of the deities. It is used as a vessel of purification, to bestow blessings and confer empowerments. There are also Treasure Vases, which contain special substances and are buried or hidden for various purposes.

Mallets or Hammers (Skt. mudgara) and a Club (Skt. gada) symbolise crushing strength or power.

Bow and Arrow refer to single pointed concentration to achieve the goal of liberation.

The Trident is a piercing weapon, its, three points also carrying connotations of the power of the three jewels.

An Arrow with ribbons around it can symbolize longevity and prosperity.

The Lasso relates to the constraint of negative forces.

A Trident symbolizes the attainment of the three Kayas (or Buddha bodies).

MUDRAS - SACRED GESTURES

MUDRAS - SACRED GESTURES

To make the tantric experience complete, actions of one's body, speech and mind are to be transformed. A typical example of the actions of the body is the practice of mudras. These are movements and positions of the hands which have profound symbolic meaning. One uses mudras to symbolise for example the various offerings, but they also convey general meanings like e.g. teaching or meditation.

The image on the left is a virtual image of the planned Maitreya statue in Bodhgaya. It happens to be an unconventional posture to depict Maitreya: his right hand on the knee signifies giving refuge and loving compassion to all beings; the left hand at his heart is in the teaching (Dharmachakra) mudra: the thumb and index finger are pressed together to symbolise the united practice of method and wisdom, and the three remaining fingers are raised to symbolise the Three Jewels of Refuge - Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. To the right is an image of the teaching mudra when performed with both hands

The image on the left is a virtual image of the planned Maitreya statue in Bodhgaya. It happens to be an unconventional posture to depict Maitreya: his right hand on the knee signifies giving refuge and loving compassion to all beings; the left hand at his heart is in the teaching (Dharmachakra) mudra: the thumb and index finger are pressed together to symbolise the united practice of method and wisdom, and the three remaining fingers are raised to symbolise the Three Jewels of Refuge - Buddha, Dharma and Sangha. To the right is an image of the teaching mudra when performed with both hands

The image on the right represents a traditional depiction of Shakyamuni Buddha, just after his enlightenment. His right hand touches the earth to symbolise it has witnessed his enlightenment (bhumisparsha mudra), and his left hand is in the meditation mudra. Sometimes the meditation mudra is performed with both hands on top of each other in the lap as the image below shows.

MANDALAS - SACRED CIRCLES

In Tibetan Buddhism, Mandalas come in two varieties; it can represent the universe (see the image left), as it is used in the Mandala Offering Ritual, where one symbolically offers the entire universe. For this, several rings can be placed on top of each other filled with rice and precious objects (see right). During the offering one recites mandala offering prayers. In the center of the mandala is Mount Meru, the central axis in the Buddhist (and Jain) cosmos.

In Tibetan Buddhism, Mandalas come in two varieties; it can represent the universe (see the image left), as it is used in the Mandala Offering Ritual, where one symbolically offers the entire universe. For this, several rings can be placed on top of each other filled with rice and precious objects (see right). During the offering one recites mandala offering prayers. In the center of the mandala is Mount Meru, the central axis in the Buddhist (and Jain) cosmos.

The best-known mandalas are part of the world of Tantra; they represent the "3D Palace" of a specific meditation-Buddha or deity. In the Tibetan tradition, they come as thangkas (scroll-paintings), wall paintings, sand-drawings and 3D models of e.g. wood or metal.

A mandala can be "read" and studied like a text and most important, be used for tantric meditation. The purpose of a mandala is to acquaint the student with the tantra, and thus allowing the student to identify with the deity and its sacred surroundings as the mandala. (See also Tantra.)

The mandala of Kalachakra like the one on the left, symbolises the entire universe in terms of planets and time cycles, as well as aspects of our body and mind, and even the practice. Deities and other images within the mandala represent for example the sense organs, the elements and mental aspects, all in a purified state. Every implement held by each deity has again its own meaning.

The mandala of Kalachakra like the one on the left, symbolises the entire universe in terms of planets and time cycles, as well as aspects of our body and mind, and even the practice. Deities and other images within the mandala represent for example the sense organs, the elements and mental aspects, all in a purified state. Every implement held by each deity has again its own meaning.

A sand mandala represents a full 3 dimensional palace, often with more than one storey. For example, the image on the right is from an actual 3D mandala of Zhi-Khro (the six bardos) with 2 stories. These mandalas are used in many ways; as a focal point of intense meditation, in the practice of actually making one, and in their destruction (like sand mandalas after an initiation is completed) to teach impermanence. In the practice of Kalachakra, one strives at visualising the complete mandala, including its hundreds of deities in perfect detail within the size of a tiny drop. This should give an idea of the level of concentration required for transforming oneself into a Buddha.... Creating a Kalachakra mandala of some 2 meters diameter, traditionally takes 6 days, employing as many as 16 monks.

A sand mandala represents a full 3 dimensional palace, often with more than one storey. For example, the image on the right is from an actual 3D mandala of Zhi-Khro (the six bardos) with 2 stories. These mandalas are used in many ways; as a focal point of intense meditation, in the practice of actually making one, and in their destruction (like sand mandalas after an initiation is completed) to teach impermanence. In the practice of Kalachakra, one strives at visualising the complete mandala, including its hundreds of deities in perfect detail within the size of a tiny drop. This should give an idea of the level of concentration required for transforming oneself into a Buddha.... Creating a Kalachakra mandala of some 2 meters diameter, traditionally takes 6 days, employing as many as 16 monks.

For a nice description of the Chenresig mandala, see this description by ven. Tenzin Deshek.

OFFERING RITUALS

Offering rituals come in many different forms, from placing offering cakes (Tib. torma) on an altar, to blessings of sacred objects (Tib. rabne), dance rituals, feast-offerings (Tib. tsog) and fire-pujas, to name but a few.

Offering Cakes or Tormas (Tib.) contain several substances with their own symbolic meaning. In India, this offering traditionally contained three sweet substances: molasses, honey and sugar and three white substances: curd, butter and milk. In Tibet, these would be mixed with tsampa or parched barley flour to make an offering cake. For specific practices, grains, alcohol, meat, or medicine may be added.  Adding five types of grains is believed to overcome poverty and famine, while the 6 medicinal aromatics are thought to overcome illness and epidemics. Tormas can have many different shapes, again related to their specific purpose. For example, typical stepped, pyramid shaped tormas are specific to wrathful deities with wavy outer lines representing smoke and flames. The colour of these sometimes match the colour of the attending deity. Cakes for peaceful deities often contain round shapes. The tormas are traditionally decorated with sculptures made of butter and colorants. For some occasions, a cross of coloured threads, believed to have been introduced by Guru Rinpoche, is added to the torma. Two wooden sticks are bound together in the shape of a cross on which coloured threads are woven to create a cobweb-like structure.

Adding five types of grains is believed to overcome poverty and famine, while the 6 medicinal aromatics are thought to overcome illness and epidemics. Tormas can have many different shapes, again related to their specific purpose. For example, typical stepped, pyramid shaped tormas are specific to wrathful deities with wavy outer lines representing smoke and flames. The colour of these sometimes match the colour of the attending deity. Cakes for peaceful deities often contain round shapes. The tormas are traditionally decorated with sculptures made of butter and colorants. For some occasions, a cross of coloured threads, believed to have been introduced by Guru Rinpoche, is added to the torma. Two wooden sticks are bound together in the shape of a cross on which coloured threads are woven to create a cobweb-like structure.

Tormas can be vary from a simple small clump, to very large and complicated, measuring up to a few meters in size. They can be used as devices to which all the evil and sickness of an individual or a community are transferred and thereby eliminated. Every year in many of the temples, monasteries and dzongs the ritual of "casting away the torma" is performed on the twenty-ninth day of the last month of the year, in some places accompanied by dances. In this way, negativities of the past year can be ended.

Feast Offerings: Tsog (Tib.) or Ganacakra (Skt.) are regarded as an indispensable means for conferring accomplishment and pacifying obstacles on the spiritual path. There are three aspects to the feast-offering: the gathering of fortunate practitioners in the feast; the outer, inner and secret sacraments of the ritual which are offered and consumed during the feast; and Buddhas - whether actual or visualised - who receive the offerings and bring the ritual to its successful conclusion. The overall purpose is to distribute merit and wisdom in the context of a specific tantric ritual.

Fire Pujas can be as simple as in the Vajra Daka practice (see the page on tantra), or can be very elaborate, like for purifying mistakes at the completion of a long tantric retreat. Fire pujas are also held to bless the ground before the construction of temples or stupas. Fire offerings can be of different types: peaceful to overcome obstacles and defilements (like usually after a retreat); increasing to expand wealth, wisdom and merit and to gain longevity, controlling to subdue harmful forces; forceful to banish negative forces.

SOME OTHER RITUALS

Consecration. Upon completion of a temple or an image for meditation, people invite lamas to perform a consecration ceremony on an auspicious day fixed by an astrologer. The main purpose of the consecration ritual is to invite the wisdom beings from their pure Buddha-fields through the power of the practitioner's meditation, the potency of the ritual and the devotion of the hosts. The wisdom beings are invited, merge into the object being consecrated, and their presence is sealed by the procedures of the ritual until the object is damaged. Thus the object is blessed and becomes sacred. A similar ritual, a deconsecration or transformation ritual, is performed when a consecrated image has to be repaired or renovated.

A very interesting observation by Sakya Pandita in his book The Right Practice of Different Views (Domsum Rabgye):

"Consecration of images is not taught in the Sutras. However, if blessing ceremonies and offering rituals on auspicious occasions, such as those performed for a king at his enthronement are consecration rituals, then one may say that consecration rituals are taught therein."

Sacred Dances are carried out by monks for various purposes; from rituals to remove obstacles prior to the creation of a sand mandala ("protecting and consecrating the site", in which interfering forces are summoned to protect the mandala site) to offering dances and acting out the life stories of famous Buddhist saints. Several monasteries are famed for their annual sacred dances.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama is known however to have warned for making these festivals too worldly; they are intended to be spiritual practices, and should not be reduced to simple entertainment.

SYMBOLISM OF SOME DEITIES

In most of the mandalas of tantric Buddhaforms, the 5 Dhyani Buddhas are mentioned; some of the symbolism related to them are found on the 5 Dhyani Buddha page.

Each image of a tantric deity, including Shakyamuni Buddha himself is filled with symbolism related to their specific qualities, see for example Meditation on 1000-arm Chenresig.

For extensive details on Kalachakra: do visit the International Kalachakra Network website.

In Tibetan Buddhist monasteries, one can often also find very aggressive-looking images, they are called the Protectors or Guardians. Many - but not all - of them are manifestations of fully enlightened Buddhas, but they appear in this wrathful form to 'wake up' the meditator and for example direct this powerful energy towards ones own problematic emotions like anger, attachment and ignorance.

From The Crystal and the Way of Light: Sutra, Tantra and Dzogchen, Teachings of Chogyal Namkhai Norbu, compiled and edited by John Shane:

"Guardians of the teachings

There are eight principal classes of Guardians each with many subdivisions. Some are highly realized beings, others not realized at all. Every place - every continent, country, city, mountain, river, lake or forest - has its particular dominant energy, or Guardian, as have every year, hour and even minute: these are not highly evolved energies. The various teachings all have energies which have special relationships with them: these are more realized Guardians. These energies are iconographically portrayed as they were perceived when they manifested to masters who had contact with them, and their awesome power is represented by their terrifyingly ferocious forms, their many arms and heads, and their ornaments of the charnel ground. As with all the figures in tantric iconography, it is not correct to interpret the figures of the guardians as merely symbolic, as some Western writers have been tempted to do. Though the iconographic forms have been shaped by the perceptions and culture of those who saw the original manifestation and by the development of tradition, actual beings are represented."

VARIOUS OTHER SYMBOLS

The scorpion refers to negative or harmful action (also menace or threat). It refers to transformation, simply said, 'if the scorpion can be transformed then anyone, and anything can be transformed.' Everyone and everything—is nothing other than the energy of the non-dual state - and therefore the power of every facet of existence can be harnessed through pure vision as a means of attainment and compassionate activity.

0 comments: